Project Proposal

Project Checkpoint

Final Project Report

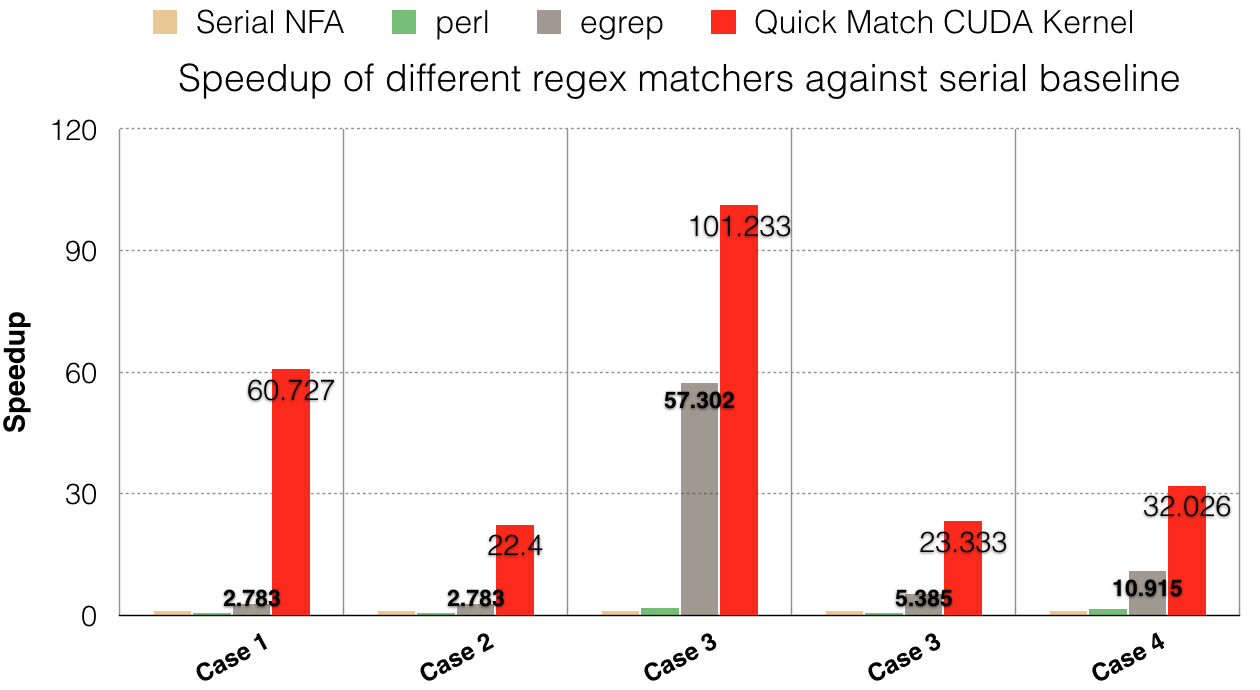

We implemented and evaluated Parallel Regular Expression matching on NVIDIA GTX1080 GPU, using CUDA. The implementation parallelizes Regular Expression matching across lines in a file. Our implementation achieves ~7x speedup over egrep and ~30x speedup over the optimized sequential implementation

Motivation

Regex matching is used in applications such as Log mining, DNA Sequencing and Spam filters etc. It would be useful to improve the performance of these applications as they often run on huge datasets. The parallelism in Regex Matching comes from the following aspects:

- Inherent data parallelism - Matching Different Lines in a file can be done completely in parallel

- No communication or synchronization overheads in parallelization as there are no dependencies between different lines

Background

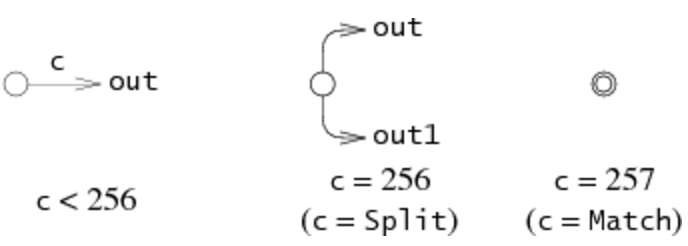

QuickMatch regex matching is based on Thompson’s Non-deterministic Finite Automaton (NFA). This algorithm constructs a finite state machine given a regex. The data to be matched is run through this state machine character by character, and the final state reached determines whether or not the string matched the Regex. The starter code for QuickMatch was taken from Russ Cox’s implementation of Thompson’s NFA Construction [2]. The key data structures used in the sequential algorithm are:

- The states of the NFA maintained as a linked list. Each node has pointers to the two possible states it can attain at any given point, and the actual character which is in that state. In terms of how this applies to our parallel implementation, the whole linked list(tree structure) will be constructed once by a single thread and be accessed(read only) by all the threads of the same block.

struct State {

int c;

State* out;

State* out1;

}

- Two lists maintaining all the states possible to be visited for a particular input string while matching a given string with the regex, one is a list currently being processed, the other is a list processed in the previous loop iteration, used for comparison. This is local to each of the threads, so it cannot be shared across threads.

struct List

{

State **s;

int n;

};

List l1, l2;

The algorithm takes in a regex to match, and matches it against the input file/s to check if the pattern exits and outputs the lines where the patterns match. (The same behavior as grep for whole-word matches, and egrep for complex regular expression matches).

The part that is computationally intensive is not the actual construction of the NFA, since this is done only once, but it is the matching function which gets called repeatedly for each line of the input and checking to see if a particular character matches the regex state. This could definitely be parallelized across different lines in an input file such that each execution unit performs the regex match on a particular input line of the file it gets assigned to (data parallelism).

The application does not exhibit any kind of temporal locality as the accesses are unique for each input character in each line, also, there isn’t a whole lot of spatial locality either.

Approach

We evaluated our algorithm on the GHC machines, using the NVIDIA GTX1080 GPU. We used the C programming language along with CUDA for our implementation.

Originally, we planned to implement the algorithm using OpenCL, targeting both NVIDIA as well as Intel GPUs. We started out by writing a simple whole-word matching algorithm which does not actually use the NFA construction approach, and got the algorithm to work and tested it out on our local Intel machine Graphics Card. The implementation of the NFA construction involves using complex data structures like struct pointers, double indirections to other structures inside a structure, and a fair amount of dynamic memory allocation to build each state and connect them together in sort of a linked list way. When we tried to implement this on OpenCL, we found that we could not do the NFA construction on the host and send it over to the GPU due to lack of same address space, and the fact that OpenCL allows copying only contiguous bytes of data from memory from the host to the GPU. So, we tried to fix this by constructing the NFA on the GPU itself, but it turns out that OpenCL v1.2 (supported on our laptops as well as the GHC machines) do not provide write access to the shared device memory, which is accessible across the kernel and the inline device functions. OpenCL 2.0 seems to allow sharing. Finally we decided not to spend more time on this and went ahead to implement the algorithm using CUDA.

We had to change the starter code quite a bit in order to make it work on CUDA. Russ Cox’s implementation did not handle whole-word matching in any given string. We had to change this so that our algorithm matches whole-word. We did this by basically starting from each character of a given line to check for the pattern match rather than just start from the beginning of the line. (The original implementation fails to match “hello” in “world hello”, as it breaks out after the first letter mismatch. We start the match at each letter of “world hello”, and finish only when there are no matches anywhere). Another major issue we faced was that the algorithm was recursive in nature. We had to change this to an iterative version so that it is amenable to CUDA. We did this by maintaining a custom stack of our own while adding new states to the NFA during its construction.

Algorithm

Our implementation on CUDA is as follows: Input: A regular expression and search file Output: Lines with a matching regex pattern

- Read the file into a buffer called ‘search_string’ (char *)

- Find the start offsets of different lines in the buffer by reading the file line by line. Save the offsets into an array called ‘linesizes’ (int *)

- Call the kernel with search_string, linesizes and the lengths of both these arrays

Match Kernel Implementation:

- In each CUDA thread block, one thread (threadIdx.x == 0) constructs the NFA from the Regex and saves it in a block shared state.

- Once the NFA is ready (read syncThreads()), every thread reads from the search string at an offset determined by its global index (blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx) and the linesizes array. i.e Thread with global index 0 will read at offset 0 till the length of the first line which is given by ‘linesizes[0]’. Thread with global index 1 reads from linesizes[0] till linesizes[1] and so on. The substring of the search string that represents a line is copied to a thread local array

- The match is performed on this substring using the NFA states present in shared memory.

For completeness and accuracy, threads process lines in batches. Batch-size = NUMBER_OF_BLOCKS*THREADS_PER_BLOCK. After multiple rounds of tuning and optimizations we found that the optimal number of threads per block is 256 and the optimal number of blocks is 80 for the Nvidia GTX1080 hardware architecture.

Results

QuickMatch implementation is compared against perl, egrep and the baseline sequential implementation. The test-cases were varied in the following aspects:

1) Size of Search File

2) Complexity of Regular Expression

3) Frequency of pattern in the file ( Many matches versus few matches ).

In this section we discuss a few interesting test-cases out of the many combinations of the above parameters.

Note:All test-cases in this section are run on the Nvidia GTX1080 GPUs on the GHC machines

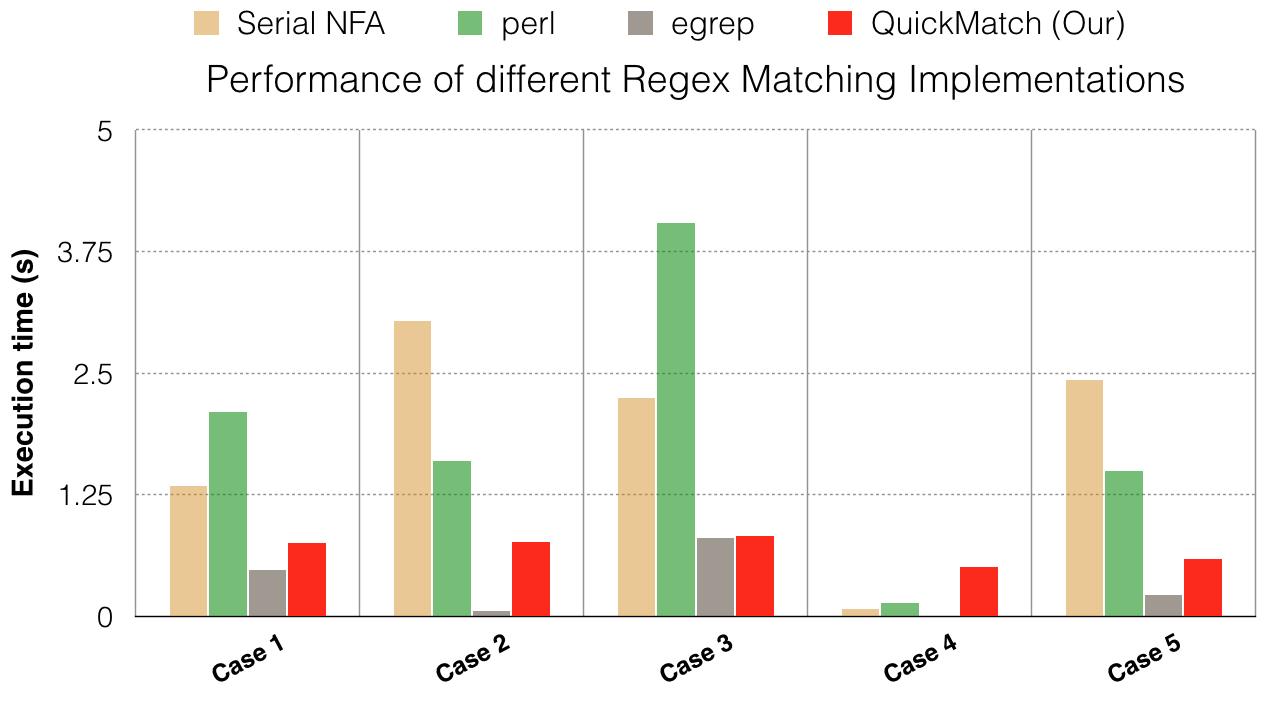

TestCase 1: Many Matches in a Sparse Matrix file

Dataset: Sparse Matrix (~160 MB)

Regex: “1” - Find the occurrence of the digit one in the file QuickMatch performs much better than all implementations (Execution time is lesser) apart from egrep. This speedup of the QuickMatch implementation can be attributed to the fact that all threads are doing almost uniform work. Almost every thread finds a match and since the line lengths are short and uniform in this dataset, no threads wait too long to exit. This uniform workload and reduced SIMD divergence boosts the performance of QuickMatch

TestCase 2: No Matches in a sparse Matrix file

Dataset: Sparse Matrix(~160MB)

Regex: “Word”

QuickMatch beats all implementations apart from egrep again. Again, this is a case of low SIMD divergence and uniform workload. None of the participating threads move towards the match state.

TestCase 3: Regex Number Match in Sparse Matrix file

Dataset: Sparse Matrix (~160MB)

Regex: 6?7?8?2

In this case, the QuickMatch implementation is on par with egrep and outperforms the perl implementation. We attribute this to the fact that this regular expression matching is highly compute intensive (a lot more time is spending in matching each line) and arithmetic intensity is higher favoring the GPU.

TestCase 4: Simple regex in Text file

Dataset: Jane Austen Novel Text (~720KB)

Regex: L?y?dia | Collins

In this test-case QuickMatch performs worse than the other implementations. This is due to high SIMD divergence (The lines are not in a uniform format. Randomness of occurrences implies that there are many “step forward - backtrack” occurrences in a subset of the threads while the other SIMD lanes are just waiting. Random occurrences will always show such SIMD divergence.

TestCase 5: Small regex in Text file

Dataset: Jane Austen Novel Text duplicated many times (~59MB)

Regex: L?y+ (Very frequent matches potentially early in each line)

In this test-case, QuickMatch performs better than everything part from egrep. While this suffers from SIMD divergence too, this regex is far more likely to match quickly in a line and exit the thread(all occurrences of letter ‘y’ will match apart from just Lydia). (This result also verifies the claim that Perl performs increasingly worse when the dataset size increases)

Result Analysis

The biggest observation from all the test-cases we ran is that the performance is input dependent. The relative performance observed will dependent on how uniform the different lines in the file are, how often the pattern occurs and the size of the dataset.

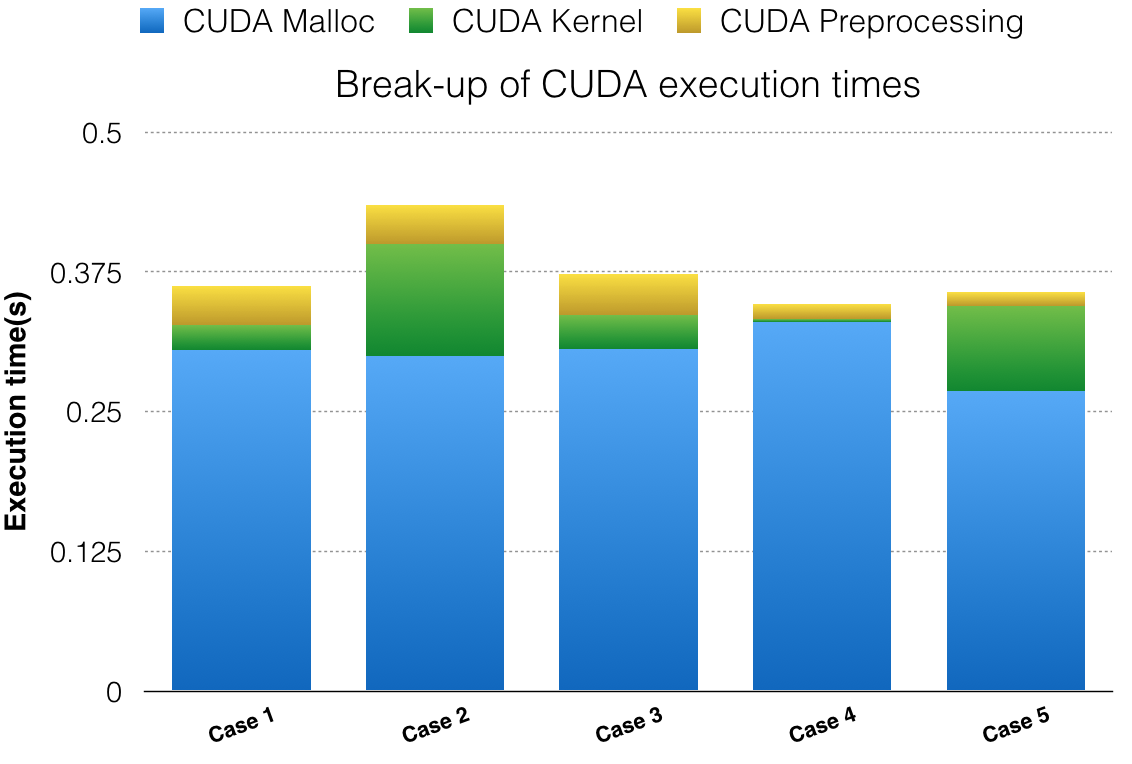

The above results suggest that while QuickMatch performs better than its baseline serial implementation, it does not outperform the CPU egrep solution in spite of exploiting parallelism. This encouraged us to look deeper into the break up of the QuickMatch execution time using NVProf and instrumentation.

The following graph shows the break up of execution times for QuickMatch for the test-cases mentioned above. We can clearly see that most of the time is spent in CudaMalloc. CudaMalloc is known to take a constant overhead of over 200ms on its first call. We can exclude the time taken in the first CudaMalloc from our performance measurements.

The graph below shows speedup of each implementation with respect to the baseline optimized( C -O3) serial NFA implementation. QuickMatch performs on an average ~7x better than egrep and on an average ~30x better than the serial implementation.

Conclusion

The high variance in relative performance for different datasets and regex inputs suggests that there isn’t one solution that fits all use-cases. This is a good argument for a heterogeous application. The application can intelligently choose between the CPU or QuickMatch implementation depending on the nature of the inputs. Alternately, files that have uniformity in lines (such as webpage logs) will perform well with QuickMatch.

References

- Thompson, Ken. “Programming techniques: Regular expression search algorithm.” Communications of the ACM 11.6 (1968): 419-422.

- Implementing Regular Expressions. N.p., n.d. Web.

TEAM

Bharath Kumar M J(bjaganna) & Madhumitha Sridhara(madhumit)